He’s been blacklisted and seen his work torn down. But the great Brazilian creator of vast gravity-defying buildings has just entered architecture’s elite.

“All space is public”, says Paulo Mendes da Rocha. “The only private space that you can imagine is in the human mind.” It is an optimistic statement from the Brazilian architect, given he is a resident of São Paulo, a city where the triumph of the private realm over the public could not be more stark. The sprawling megalopolis is a place of such marked inequality that its superrich hop between their rooftop helipads because they are too scared of street crime to come down from the clouds.

But for Mendes da Rocha, who received the 2017 gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects this week – an accolade previously bestowed on such luminaries as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright – the ground is everything. He has spent his 60-year career lifting his massive concrete buildings up, in gravity-defying balancing acts, or else burying them below ground in an attempt to liberate the Earth’s surface as a continuous democratic public realm. “The city has to be for everybody”, he says, “not just for the very few.”

His most celebrated work, the Brazilian Sculpture Museum (MuBE) in São Paulo, completed in 1995, is the result of trying not to make a building at all. The site is instead conceived as a terraced sculpture garden, with the museum’s galleries located underground and a concrete canopy flying overhead, a jaw-dropping 60-metre long levitating beam. When asked why he didn’t opt for the more obvious solution of a building with a sculpture courtyard in the middle, he simply replied: “It would hide the things that happen there, and the city would be excluded in some way.”

The ageing Marxist, with his baggy navy blazer and bristling white moustache, makes for an unlikely addition to the list of famous names chiselled into the walls of RIBA, alongside Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry and Jean Nouvel. In the past decade Mendes da Rocha has been showered with awards, winning the Pritzker prize (architecture’s Nobel), the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale and Japan’s Praemium Imperiale award last year, but he doesn’t fit the stereotype of a globe-trotting “starchitect”.

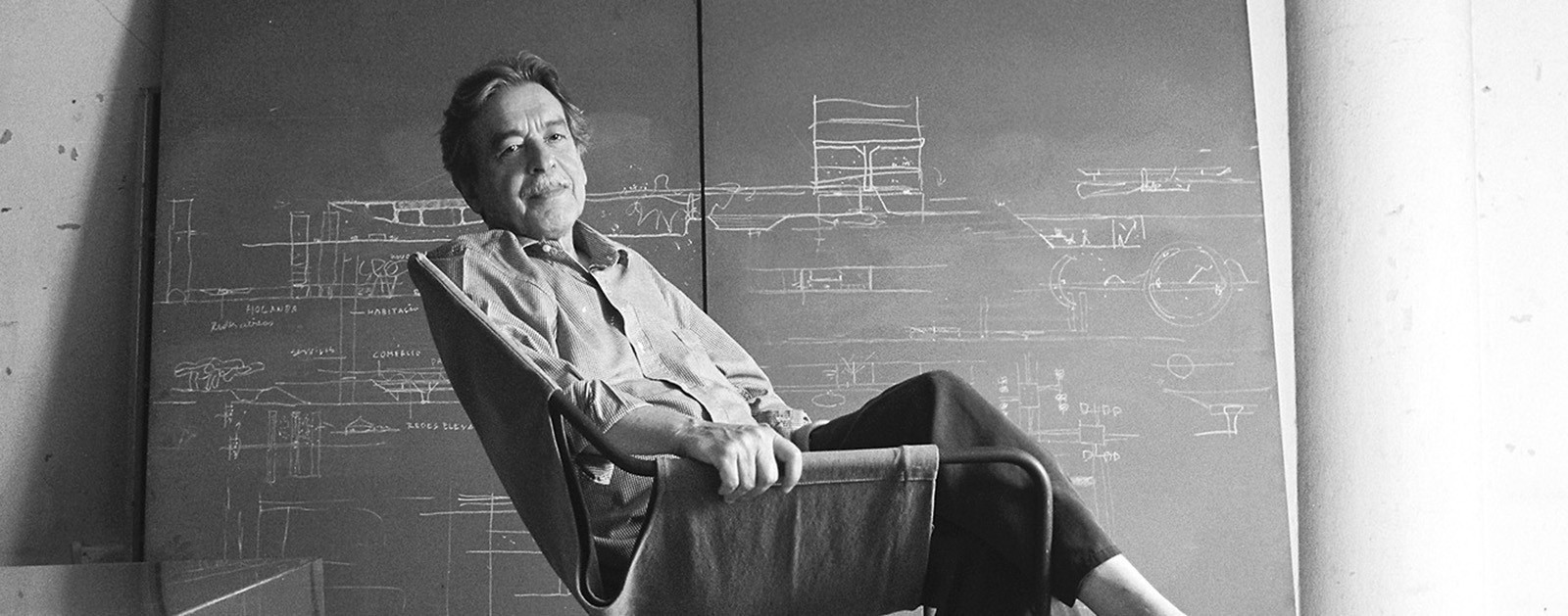

He maintains an office of one, based in a modest room in São Paulo’s crumbling 1940s headquarters of the Institute of Brazilian Architects, lit by a naked lightbulb, its walls lined with blackboards on which he sketches his structures with extraordinary freehand precision. He has built little outside his home country. When he works on projects, he collaborates with a number of different studios around the city, many of them run by former students.

“I don’t have any desire to manage a business”, he says. “There is so much administration in the world these days, and I am delighted my colleagues are willing to do it. Not having my own office gives me the greatest freedom – to do nothing if I want to!”

It is a unique model of practice for an architect of his stature, and he may make light of it now, but this unusual setup stems from the fact that he was forbidden from running his own office in Brazil for almost 25 years.

When the military dictatorship came to power in 1964, he and his fellow left-leaning architects were dismissed from their university teaching posts and had their architectural licences revoked. Many fled the country: Oscar Niemeyer went to Paris, where he designed the Communist party headquarters. João Batista Vilanova Artigas, Mendes da Rocha’s closest colleague and mentor, left for Uruguay. But Mendes da Rocha stayed put.

“I couldn’t leave”, he says. “I had five children and I didn’t want to abandon the country. It was a dreadful time. I had friends who were arrested and murdered. Brazil is still living with the consequences of that period today – our current state of crisis is a hangover from those days.”

Blacklisted for almost half his career, Mendes da Rocha’s rise to prominence is all the more remarkable. He first made his mark at the age of 30, a toddler by architects’ standards, with his startling scheme for the Paulistano Athletic Club. Photographs of the building were widely published on its completion in 1958, showing a minimalist concrete UFO: a disc held aloft on six slender blades, each sharply chiselled to express the geometry required by the thrusts they must oppose. Pairs of cables, strung from the top of each concrete fin, support a suspended steel shell, sheltering the space of the gym below, keeping the ground open to retain views through the space. It is as stripped down and sparse as possible, a pure diagram of the means of enclosure.

In its bold structural simplicity, it set the tone for what would become a series of projects driven by clear constructional logic, each building generated by a singular idea about how to support a roof, or how to free the ground. His São Pedro Chapel, built in Campos do Jordão in 1987, doesn’t look like it should stand up at all, consisting of a hefty concrete slab sitting on top of a delicate glass box – the whole thing magically cantilevered from a single column in the middle of the building.

The architect says he learned technical discipline from his father, who was an engineer and designer of hydraulic works and port facilities. Their shared love of infrastructure is evident in the raw concrete forms of Mendes da Rocha’s buildings, with their echoes of dams and flyovers. This pragmatic attitude lay at the foundations of the Paulista school, a group that included Artigas and Lina Bo Bardi – together known as the “Brazilian brutalists”. They favoured chunkier massing and rougher concrete finishes than their Rio counterparts of the Carioca school, typified by Niemeyer’s smooth, curvy white forms. In contrast to the formalist approach favoured by some contemporary architects, who come up with a shape and hand it over to the engineers, Mendes da Rocha insists that “you can only imagine what you know how to build”.

His Brazilian pavilion for the Expo 70 in Osaka was the most daring demonstration of his engineering prowess, a vast concrete waffle slab levitating over an undulating landscape, which rose up to support the great weight of the roof at just three delicate points. Though intended to be temporary, it was so well received that the local university wanted to keep it as a dance school for children. The Brazilian military government refused and had it torn down.

However fleeting, the pavilion embodied what Mendes da Rocha saw as the “founding trait of architecture”, as an “instrument for configuring the land”, an idea he would develop in his competition entry for the Pompidou Centre in Paris. This imagined a generous public piazza sliding beneath the building, the floors of the gallery stacked up above as a series of sloping terraces. He lost out to Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s pipe-clad refinery, but he finally got to build something of a similar scale in Lisbon, in the form of the National Coach Museum, completed in 2015.

Located near the gothic confection of the Jerónimos Monastery in Belém, it feels a little out of place – a great white aircraft hangar jacked up on fat concrete columns, as if lost in translation from the brasher streets of São Paulo. Still, it might soften with time and use. As Mendes da Rocha insists: “One never builds something finished.”

Words

Oliver Wainwright

Source

The Guardian